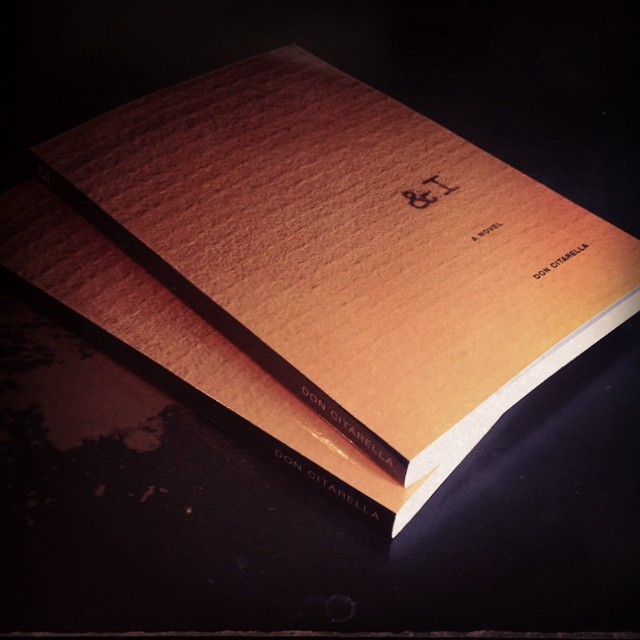

Earlier this month, I finally finished a novel that I’d been working on for the greater part of three years. &I is a study in self-identification as a reflection of others—twins, in particular.

In researching how to find a publisher for the book, I learned that I should create a cutting and submit it to online literary contests. Below is that cutting. If you know anyone in the publishing industry that may be interested in reading the full manuscript, please don’t hesitate to drop me a line.

We are all kings, today. We are royalty. For the right price, each of us can be loved as God loved the dynasties of yesteryear.

I stood before the colossal doors of Palazzo Zen on the northern edge of Sestiere Cannaregio in Venice. I leaned in exhaustion, awaiting the woman who’d grant me open-ended access to my own personal palace where I’d continue my search for Worm. After an eternity of waiting, I heard the loud clanking of a lock’s ancient tumblers and the door lazily swung inward. On the other side was an elderly woman, a cigarette blooming among the wiry hairs on her lower lip.

“Signor Wood?” she hollered. I nodded. Despite her thunderous presence, the woman’s stature reluctantly teetered around 4-feet. As the acqua alta receded from the Palazzo’s courtyard into Campo dei Gesuiti, she hobbled over planked risers that led us inside the estate of the late Famiglia Zeno. I imagined that one misstep would send my tiny guide hurdling through the dwindling waters, only to be swept out to the Adriatic. But for an aged arthritic, she was unquestionably agile. I’d learn in the following weeks that centuries of hardship on the swampy armpit of the Italian peninsula had created a population of rigid constitutions that remained steadfast in the Venetians’ later years. “Wood.” she repeated to herself. “Legno,” she muttered and choked on yellow, emphysemic phlegm. “Il tuo albero di famiglia ha abito in la sestiere San Marco. You family,” she attempted in English, “You family are displaced.”

After pointing with gnarled fingers at the intricacies of the lower level’s deliveries, lighting, and heating, she allowed me to ascend the stairs to the second floor on my own. I rested my bag at the foot of a massive bed below a fresco of swirling angelic visions and collapsed on a pile of dusty quilts. Fatigue overtook me and I fought the urge to lay back in impending unconsciousness. Instead, I imagined my brother wandering the streets below. How did he spend his days in the Queen of the Adriatic, the city of masks and bridges and canals? Was he overcome by inspiration to write? Did he walk the cobbled maze hand-in-hand with his Casanova, regaling the Czech youth of another Thomas and his Death in Venice? Did he think fondly of the world he left behind? Of Pine Harbor? Of me?

Before exhaustion and guilt could consume me, I mustered the strength to rejoin my host at the foot of Zen’s winding marble stairs. She sat on the third step with her knees and the many hems of her dress pulled up to escape the lapping tide a few steps below. As I descended, I watched her stare out at the shadows and glimmers that caught the water of the courtyard, mouth agape, enjoying the mysteries of her city. She heard my footsteps and struggled to rise to her feet. With one hand on the rail, she extended the other for balance. This waxen, pallid relic of La Serenissima, proud and defiant against age, gazed back with yellowed glaucomic eyes. In that moment, I found her striking. She exuded a strange femininity insolent to the notion of time. She was my mother, and Leslie, and the strawberry blond that plucked away my virginity, the high school virgins that allowed me to pluck theirs, each striving starlet that glittered their way in and out of Broadway’s footlights and countless forgotten girls in between. In my weary, jetlagged daze, she was the foreign mystique of Venice, of Prague, of Europe. I saw what enchanted Worm to her shores and firmly led patriots to the lives of expats. I was falling for her. I was falling for Palazzo Zen. I was falling for the old world.

“Lei e bellissima, si?” she said. Yes, I thought. She is beautiful.

The woman handed me the key and I walked with her across the plankway toward the world-beaten doors that led to the street. She hobbled off in the direction of the Grand Canal and Ponte Rialto, where I knew the real estate office was located. My resolve ran dry and knew I could fight off sleep no further. Still, I meandered through the campo to collect my thoughts and spend these last moments of consciousness letting Venice saturate my senses. Shopkeepers squeezed mops and emptied buckets of murky water from windows and sotoportegos. Children in rubber boots sloshed through puddles and kicked water at circling seagulls. Clusters of Venetians stood uncomfortably close, their cigarette smoke entwining as it rose and flitted on the breeze toward the sea. Finally, when exhaustion would no longer be abated, I turned back toward my frescoes and marble stairways and closed the doors to the rhythmic lapping of gondolas and acqua alta. The thought of rolling my own cigarette was bested by my addiction for sleep and as I collapsed in surrender, I stared at swirling orgiastic seraphim and let my remaining thoughts dwindle on the decadence around me. The denizens of La Dominante, who dutifully maintained their floating city and rented out palaces, afford us all the luxury of royalty. We are all kings, I thought as sleep enveloped. Each of us.

* * *

It was halfway through my third bellini at Cipriani’s that I first thought I spotted Worm, traversing the beautifully cobbled Calle Vallaresso. I threw a crinkle of Euros at Giancarlo and flew off the stool toward the street.

I’d set-up shop at the corner bar following the depression and despondency of a failed weeklong search for my brother. My initial intent was a sample of the house grappa to revitalize my spirit, strengthen my resolve, and whet my whistle. But after the bartender began topping off my glass and recommending a variety of house favorites, Harry’s Bar became more of a destination than a refueling station. As one of the first people that recognized me following the success of Blithe Brother, Giancarlo fed me a steady diet of praise and booze. He also knew seemingly every girl in the sestiere and could accurately categorize them by relationship status, desperation for companionship and, using his words, la capacità di conquistare. In short, the barman easily exacted my three vices—alcohol, egomania and women—and used them mercilessly against me. So when I caught the tangled ponytail bobbing out of my periphery, it woke me from the dreamlike stupor of the lotus-eaters and sent me reeling back to reality and the bar’s front door.

The street was a bustle of activity with tourists fawning over the snowy remains of the new year. Between the aging stones, decades of rotten Carnevale confetti clotted in their icy veins. Fissures of fango sedimented with the fetid, fermented mixture of the refuse of the bar. I steadied my gait with a hand on the wall and trudged past the bundled tourists and venetians with my eye on the ponytail.

It was easy to tell them apart, the locals. They moved in tight clusters, hedonistically clinging to hirsute coats and chain-smoking Galoise cigarettes. The impenetrable masses of smoldering fur roved as feral packs of hellhounds. Though swaddled in sables, slaggy, serrated edges protruded from their seams. Their designer dogs, their nicotine-stained nails, even their Slavic-influenced accents, were flesh-piercing. Every manicured inch was cold and imposing and, by God, I was aroused by almost all of them.

The ponytail jogged past the jewelry store where I once found a conquest, ogling Murano glass creations in the shop window. It continued down the block, turning right before the Hotel Casanova, where the conquest had led me to her room. I dodged a portly couple in matching backpacks and careened off a bale of Japanese snapping tourists. Rounding the corner at Caffé Florian, I lunged for Worm but realized that he was no longer in sight. Frantically scanning the traffic, I watched it funnel through the alley into Piazza San Marco. I knew I had to spot him before he entered. If Venice was already tourist hell, San Marco was Pandemonium City. Their numbers rivaled those of the pigeons in the air, the gondolas on the canals, the mosaic tiles on the basilica’s façade. It was already too late. The ponytail was gone.

In defeat, I succumbed to the current of sightseers and allowed myself to be sucked into the square. There, the masses pulsed through chaotic arteries as if propelled by capillary action. The ebbs and flows only subsided when I was stationed at the head of Europe’s most beautiful drawing room, dotted with pigeon food vendors and tourists hungry for memories. Unbeknownst to most, the sky had erupted in a curtain of icy palpable fog that settled on the piazza. For over an hour, I meandered through the evanescence as one of a thousand snowflakes in a snow-globe. I knew how much Worm’s disappearance affected me. But it wasn’t until I allowed myself the hope of his return that I realized how badly I was hurting without him.

An anciente sat frozen among the tourists. At first I thought he was a performer, imitating statues of the dead that were, in turn, imitating the living. But most of the buskers were romani, hiding Gitano features behind gilded Carnevale masks and lavish silver headdresses. This old man wore a tweed suit, weary and defeated in a long struggle with time and moths. And unlike the statues and gypsies, he was moving. He carefully powderized a slipper of biscotti between arthritic fingers, inciting a riot of pigeons. His gaze remained locked on one of the birds that tottered in the scramble for crumbs.

I stepped closer as he slowly lifted his unoccupied hand and raised it to shoulder height. He was a mariner, angling an invisible harpoon. He expertly bided his time for the moment to strike, the perfect configuration of flutter and inattention, winged confusion, obfuscation, and bedlam. When the moment arose, he lunged forward with speed belying his age, and plunged his hand amid the startled scatter of birds that instantly and frantically dispersed, save one. The bird lay with his cheek to the cobblestone, pressed to submission. Its only movement was the petrified darting of its visible red eye.

The Italian now returned to a pace more apropos. He casually lowered himself to the seated position, against the balustrade, and inverted the pigeon in his hands. The bird craned his neck toward its breast, inspecting the callused thumbs that secured it. The captor gently pressed his knees against the folded wings of the supine pigeon, effectively freeing both hands and locking the bird in place. I feared for the bird’s life and cautiously approached to argue its release. The old man noticed my arrival, dismissing and disarming me with a smile. He reached into his pocket and produced a leather handkerchief. Laying it on the stone at his feet, he unwrapped it, revealing a minute set of utensils, similar to those of a clockmaker or a dentist. There were prongs and picks, styptic pencils and sterile pads, and an array of near-flattened ointment tubes that resembled molted snakeskins.

“E Dio dice: ‘Voi comanderete sui pesci del mare e sugli uccelli del cielo e su ogni essere vivente che striscia sulla terra’.” This man became, to me, an Italian Tom Waites. Despite my inability to understand a word he said, I was able to appreciate the melodic timber of his voice. I looked at him, puzzled.

“Inglese?” he grinned, and I nodded. “Americano?” he asked, producing a second nod. “God telled men to be good to His creatures,” the old man said. He drew to his eye a pair of tweezers he’d retrieved from the handkerchief, and inspected them with careful, meticulous precision. Protected from the freezing rainfall, but not the unforgiving wind, I watched him deftly clasp the frayed edge of twine wrapped deep in the flesh of the pigeon’s ankle. He unwound the string slowly as the bird’s eyes pled with me for salvation. I could see it pull from the deep and bloody recesses where it threatened necrosis and amputation. “I think, sometimes, are His angelli sent to guard this piazza.” He looked into the eyes of the pigeon in what seemed a vain attempt at assuaging its fear. “The touriste are not so careful,” he said to the frantic bird. “Sometimes, is possible to grant the salvazione.” When finally the string was freed of the bird, or perhaps the other way around, the man traded the tweezers for a small, coiled tube of ointment and gently worked some balm into the ruddy canal that encircled the bird’s ankle. “Sometimes, I can no do The Signor’s work, but Death’s instead. Tristo Mietitore.” I looked at him confused. “L’uomo con la falce?” he made the gesture of a scythe and I nodded.

“If I can no mend them,” he said. “I take them there.” He pointed to the icy, lapping waters at the other end of the sotoportego. Chunky floes undulated on the surface like miniature marshmallows. “By time I finish speaking salmo vente-tre, the angel is drowned.”

Inborn in Worm’s poetic heart, he disappeared into a city disappearing unto itself. Around my ankles lapped the aqua alta, which had grown ever more present throughout the years. Venice was not only sinking, but edging each year a few more millimeters eastward into the Adriatic. She’d grown tired of bearing people tired of bearing themselves. She shouldered the weight of her existence, of her history. She was the sinking library, where the architect had forgotten to factor-in the weight of the books. She was the telephone pole bowing to the burden of a million rusting staples. She was me. She struggled beneath her aging, decaying reputation, fighting to retain a foothold among the shimmering monoliths rising in the Middle East. For centuries, her only crime was that she cared too much. And now, exhausted of the burden of attention and the sordid deeds of her past, she longed for eternal slumber beneath the chilly comforter of the sea. Was that why you came, Worm? Is that why you’ve brought me here?

The icy mist formed in gelid chunks on my head and clung to clumps of hair as I tried to brush them free. Frozen, beaten and depressed, I retreated back to the Florian for an espresso. It was a caffé that I hoped to frequent on a nicer day, with quaint outdoor seating perfect for people-watching and scouting my next conquest.

Pushing past the susurrus of hot air, I entered and wended my way to the counter to wipe my face with a wad of napkins. The barista took my order with a friendly demeanor, performed his duties mechanically, and watched with apathy as I shook the ice from my collar and shoulders. My eyes stung, my throat burned, and my heart ached. I had no proof that the man I suspected of being my brother was actually him. It had been four years since I’d last seen his face, so I recognized the absurdity of spotting Worm and then losing him at this very caffé an hour earlier.

“Paghi ora o te lo metto sul conto?” the barista asked. I shook my head to indicate that I didn’t understand. A look of whimsy met my eyes before he studied my hair and smiled. “Did the barber also cut off your Italian tongue?” he quipped. “Do you want this on your tab, Guillermo?”

* * *

I stood at the Italian coffee counter at the Florian and choked back two consecutive shots of tequila, followed directly by two shots of espresso. My palate moaned of the unexpected onslaught by two independent, but equally volatile, magmic flows, of heat and heat. My temples were overcharged with double cracks, begging moderation for my smaller, less tolerant frame. You’re no longer driving a Humvee, it seemed to say. We cannot handle this octane. But the café was empty and the reliability of a time-tested method for instant sobriety was required. I waited for the panacea to work and collapsed into faux-rattan chair furthest from the door.

From this vantage point, I could see everything. The archetypal wall of crackle-cured vessels adorned with miniature silver spoons. Various philters were arranged by size, sweeping from Galliano’s luxuriously feminine legs to the portly constable of Chambord. The counter boasted a svelte midriff of butterscotch marble, similar to the frozen torrents of the nearby basilica’s floor, and was shod in a kickboard scuffed by eons of Burano leather. My head swam in the heat of the room, while pungent bitters swirled waist-high. It wasn’t the fear, or the exhaustion, or the overwhelming excitement of the circumstances that brought me to tears. It was the sheer and simple fact that I was about to be reunited with my brother. At a loss for all natural physiological response, my body’s only reaction was to weep, uncontrollably. I allowed myself a moment of childishness, blubbering in the corner. Silhouettes of tourists pirouetted through the foggy windows to the melodic tune of cream being aerated to foam. It was a mesmerizing display, I admit, and I found myself captivated by the play of light and shadow. It was long after the clink of coins settled in the till, and the customer had retreated to the washroom that I realized the barista and I were no longer alone.

I wiped my face and cursed my stupidity. Surely this reunion had enough weighing on it to tolerate one more act of foolishness. The peppery gust of agave that billowed as I blew my nose watered my eyes anew. I straightened my collar and ran shaking fingers through my hair as my heart pounded. I wasn’t used to grooming it yet. Would he recognize me without my former hairstyle? Would he mock my physique, the pallor of my skin?

A toilet flushed and the man stepped out of the bathroom. His broad shoulders stroked a confident stride back to the counter where his cappuccino was waiting. He set a fedora on the bar and leaned in to our host. I heard a whisper in Italian and watched the barista thumb his gaze in my direction. With sheer luck, I bested the lump that was growing in my throat, swallowed it down, and returned an ersatz look of apathetic intrigue. The man turned around. It was not my Worm. But he approached me with the unsettlingly affable smile of an old friend.

“May I sit?” he asked in lethargic Slavic syllables. I sat motionless. My guest looked toward the chair and nodded, gently. And it was only when I acknowledged the chair’s existence that he swept himself into it with a huff. His coat billowed as he settled, and a plume of cigar smoke emanated from between the layers of tweed and worsted wool. I watched him gingerly collect his lapels and flatten the ends of his scarf, stroking them against his chest as though pacifying a ferret. “My name is Tomáš,” he said. Though before he even said it, I knew this was my brother’s lover. His voice was confident and embracing and years had passed since the last time I felt the familiarity of a stranger who misattributed the informal demeanor owed to Worm. His face was youthful and painted in the blush of a hiemal palette. His eyes were grayish lunettes, glowing lazuli windows that hung like half-moons from a strong, chiseled brow ridge. The carefully groomed moustache tussled a glistening pogonip as he spoke. “William said you’d be here.”

Tomáš sipped his cappuccino and I watched crystals melt from his upper lip. Was it his age—a late pubescent at best—that drew my brother to him? Was it his sartorial grace commingled with a seeming knowledge beyond his years? Were I ever in question of my sexuality, I confess that he might sway my indecision. But I knew, deep down, that Worm’s selection of this boy had more to do with a virginal, tragic youth than with the boy himself. And my affection for my brother, whom Tomáš had intimately known, drew me in further.

“We together saw your play,” he continued. “On the night of opening, you took my hand and thanked me for my…attendance.” A quizzical look must’ve betrayed my face as he smiled and sipped his drink further. I noted his delicate fingers, knuckles devoid of hair or protrusion, and watched him thoughtlessly spin his cup on its saucer. “You were terrible. It was only after we returned to watch on the night of closing that I understood William’s…decision to have you in this role.” My heart leapt. Through the last three years, my brother had flown back to see me twice. I suspected his presence through the run, but my furtive searches through countless curtain calls were unrewarded. Worm had seen me perform! And with some satisfaction, I thought of his trust in my skills, my interpretation of his words.

The café doors tinkled open and a gush of air sifted through my clothes and hair. I nearly erupted from my chair to catch site of the visitor, a middle-aged signora, impossibly wrapped in sable fur and rosary beads. Still I searched, untrusting of my eyes, to make sure it wasn’t my brother. It was only after some certainty that I reseated myself, ignoring the obvious humor in Tomáš’s eyes. Embarrassed and fatigued I unfocused my eyes, breathed in deeply—once, then once again—and steadied my shaking hands. I smelled the subdued aroma of citrus cologne commingled with the musky acridity of cigars. Finally, I looked up to witness my guest readjust the scarf closer to his slender hairless neck, the chill reflected in his hyaline blue eyes. Fantastical imaginings of my brother and this boy arose suddenly and I felt unsettled by my level of ease about them. I quickly dismissed the image of my brother’s head cradled against that neck—nuzzling glabrescent warmth, inhaling amaroidal aromas. The huzzbuzz of patrons at the counter returned me to the excitement of the moment and I allowed myself to linger on the enjoyment Tomáš had from my final performance.

“He doesn’t want to see you, your brother,” Tomáš said. His eyes were cast to the conversation at the counter. He tossed out the words as if meant for the wintry air, the barista, the walls of the café, anyone but to me. “He considered you dead for years. I can’t say that I blame him after your opening performance,” he chuckled. His levity did nothing to assuage me. And only after a turgid, uncomfortable silence with my glare locked steadfast in his periphery, did he return my gaze. “It was after I heard your…requiem, on the final night that I believed you had…reformed your ways. The thing you did, it wasn’t only torturing him. It was killing you, too.”

I looked down, penitent and afraid. All I’d prayed for in the past three years was to apologize to my brother’s face. I wanted him to see how it pained me to believe he hated me. Unworthy of his love, unfitting of his trust, all I wanted was to beg his forgiveness and let him know how truly sorry I was. It was all that I could do to fight the impending tears and the torrent of contrition that teemed behind my lips. I watched Tomáš rotate his cup and somehow kept my silence.

“You’ve wasted away. I’ve watched you for the last two weeks. You drink yourself into a…stupor night after night. You take no comfort from the delights of Venetian cuisine, the beauty of the women. You smell like a…cistern, you look even worse. I see my William’s face on your body and my heart grieves for you both. What is it you need to be whole, again?”

I looked into his eyes and found only the glint of a compassionate, fraternal smile. That was all I needed for the dam to burst. My mouth opened but the only sound I could utter was a froglike whoop. Again I tried, but words failed me. My chin felt slack as I swung my head from side to side and drove the tears from my eyes with the palms of my hands. The harder I tried to confess, the louder my moans became. I sputtered and choked, my frustration and nausea growing. I opened my eyes to a bleary world off-kilter, and a café of silent people staring. A caustic concoction gurgled in my throat and I burst from the table, upending chairs in my wake, and erupted to the icy cobbled street. There, I confess, kneeling in the frigid, murky mire, I emptied my stomach into a snow bank. I continued to wretch and cough—as my legs soaked to numbness and tourists gawked and snapped pictures—until the spasms ceased and exhaustion and hypothermia set in. I lay on the street and stared up at the ambling flurries and prayed my brother was far from witnessing the sorry, pathetic state of his brother.

Only after finishing his cappuccino did Tomáš find his way to the street. He found me lying supine, shivering in a puddle, and staring past the chimney pots. I watched him skirt my vomit while casually lighting a cigar. He took a pull on his Monte Cristo and exhaled a blue smoke past my field of vision. The putrid stench threatened my stomach anew.

“When you’re ready,” he said, directed toward the wind, “I’ll take you to your brother’s house.”

* * *

It was with both elation and mortification that I found myself following Tomáš through the front doors of the Hotel Casanova. Earlier in the week had I, through the very same doors and in characteristic crapulence, tailed a girl to her room. Giancarlo had pointed her to my attention, a wobbly straggler bedecked in frills and a Carnevale mask, feeding Euros to a hungry payphone. Her ample bosom billowed out of a vermillion lace corset lined with fire engine red trim. January was far too early for locals to be dressed in the holiday garb, far too cold for that amount of visible skin, as she teetered down to recover a lost coin. Were I not insanely inebriated, the penitent might’ve bested the matador in me. But I saw red and took the Casanova mask from Giancarlo’s outstretched hand. The stateside call to her father was short; through slurred promises in a baby-like voice, she assured him of her wellbeing and good (pre-Lenten) Christian behavior. I approached her from behind and leaned in close, in time to hear her father say he loved her. Ti amo, Casanova whispered to her ear. We never even saw each other’s face.

This time, I wore no masks. Stripped of the effigy of the hotel’s eponym, pride, and any sense of self-worth, I entered the lavish décor of the Casanova’s lobby. The acrid burn of vomit was corroding my windpipe and I used this as an excuse for silence. In the wake of Tomáš’s cigar smoke, I passed reproductions of stoic, ageless doges, lion-griffin offerings to the God Sandon at Tarsus, and chiseled virtues of Temperance, Fortitude, Prudence and Charity—virtues I’d lost years before.

Tomáš led me up two creaking flights, past an aging cleaning person that exchanged Czech pleasantries and the door that I thought belonged to my Henriette. The top floor of the hotel claimed no other doors but one. My guide turned a key in the lock, pushed the door ajar, and stepped to the side. Unfathomable fear gripped my ribs as I approached. It was as though a swarm of congers chased each other through quivering bones, with vicious disregard for the tender viscera beneath. I took a deep breath and reached out to push the door open.

“Your brother is not here, of course,” Tomáš mused. “Step inside.”

With almost relief, I looked to my host for explanation. The day’s events left me weary with anticipation; despite the respite from impending disappointment, I just wanted the reunion to be over. Even if Worm had no kind words for me, quickly let me hear them. End the misery. Some degree of exhaustion must have registered on my face. For a moment, Tomáš expressed a look of compassion, before walking past me into the sunlit master suite. With one last breath, a moment to survey the room’s vacancy, I obeyed my host and stepped inside.

The décor was indeed Worm. Whereas I’d commandeered and slathered our Pine Harbor room with posters of Jose Canseco, Deion Sanders and Ryne Sandberg, affording him very little space for his ephemera, the walls of the Casanova master suite were deliciously devoid of clutter. Stacks of books lined the perimeter of the east wall. The west wall bore a kitchenette and threshold that framed a chiaroscuro hallway. The south wall boasted two enormous windows, echeloned by equally impressive, Wrightesque straight-back chairs. On the windowsill, a scintillating vial filled with foreign herbs in green liquid projected verdant splotches of light across the room. On the North wall, behind the door we entered, was Worm’s desk, over which a great array of index cards were tacked in perfect symmetry. I approached gingerly and attempted some of the inscriptions, but found I could read none. Smattered in shards of emerald light, lay a dustless square at the center of his desk approximately the size of a MacBook Pro. The closet and kitchen cabinet doors were open, revealing nothing perishable. The coat rack, by which Tomáš now hung his gelid scarf and fedora, was previously vacant as well. If my brother were out, it seemed his return would not be anytime soon.

But, slowly at first, I felt a comfort arise from years before. The hibernal weather ushered the room’s hermetic seal, locking in a lingering aroma. It was a scent I knew well: a complex suspension of grapefruit with top notes of mint and blood mandarin, submissive, yet virile middle notes of cinnamon, and the striking base notes of leather, white wood, amber, and patchouli. It was Worm’s signature scent and it languorously flooded my nostrils with nostalgia and love. I took a moment to breathe him in. How many handshakes had it wafted by my nose? How had it managed to permeate the plastic weave of the passenger seat of my truck, long after his departure from Pine Harbor? How is it that pheromonal memory now irrigated my eyes and drew taut the corners of my lips? My God, the sweetest, most agonizing aroma circumvented my lungs and mainlined to my heart. Words fail me, dear readers, to describe how thoroughly and equally it revitalized and enervated me. Simultaneously, it raced and arrested my pulse. It burned in me, only to suffocate in its own fire. It infested me, only to devour itself to nothing. I gorged on it, to discover myself hungrier with every unquenchable breath. With my struggle against the addictions of tobacco, alcohol, and women, I’m grateful that a narcotic could never be manufactured from purgatory. Had it not disappeared in a zephyr, this inhalant of fraternal contrition and love, I would’ve surely overdosed on Worm. Is there someone whose scent overcomes you this way? Tell me—because I honestly must know—how is it that you’ve survived?

I stood silent, for a while, attempting to make sense of the episode. I physically shook my head in disbelief, and tried recall the last time I’d smelled him. Had it been present in the crowds at the Player’s and Playwright’s Initiative? Was it lingering in the streets of New York and Prague? Was that the unidentifiable sorcery that ambushed me at the Florian?

I avoided eye contact with my host as I waited for the silliness that overtook me to evaporate. Walking to the window, I looked down onto a miniature courtyard and sotoportego. A disused well erupted from the center like a surfaced Soviet Kalev class submersible, painted with age, graffiti, anachronism, and pigeon scat. Absentmindedly, I fingered the submarine world of the green bottle.

“Do you…take Absinthe?” Tomáš asked behind me. I looked down to see that, indeed, the bottle was adorned with fading sticker denoting the potent, green elixir. I’d never tried it and was certainly in no mood to experiment, but I let him take it from my hands. He pulled two dusty glasses from the kitchen cupboard and held them close in inspection. Shaking his head, he turned on the water and began to scrub them.

Upon his return, he filled one of the behemoth chairs and motioned for me to take the other. I sat mesmerized, absently rolling a cigarette as I watched the ritual of his tabletop alchemy. He then filled both wide-necked rocks glasses with two measures of the pond-scum slurry of alcohol and herb. Atop the glasses, he placed slotted miniature spatulas and lined-up their handles to overlap. Atop the spatulas, he pressed camel-colored cubes more reminiscent of beef bouillon than sugar. In one fluid and expert motion, he dowsed the cubes and spoons akin to a Pastis sous-chef, drizzling Saint-Honores with Gran Marnier. The display was complete, yet lacked one crucial element. I sparked my cigarette as he pointed to my Zippo. “You,” he smiled, nodding toward the glasses. I carefully ushered the flame to the nexus of the spatula handles. A green flare leapt to life, traveling to the poles and igniting the sugar cubes. They sizzled and caramelized quickly. “We wait for the handle’s flame to…quench.” It did. I watched him stir with savage syncretism, the super-suspension of disintegrating sugar, alcohol, herbs, bitters and, presumably, wormwood.

The glass was warm to the touch. I aped my host’s casual sipping and allowed the pungent lava to slowly serpentine around my tongue and down my throat. It disappeared only to re-emerge moments later, snaking though in my brain. I must admit, the sensation commingled with cigarette smoke, was quite exquisite.

“He doesn’t want to see you,” Tomáš said, puncturing my reverie as though reading my dirty thoughts. I stared deep into my glass, letting the words act as a chaser to the absinthe. “I have, over many conversations in these very chairs, politely recommended he be…erm…merciful, I believe is the word. I do this not for you, but because I can see that he is not happy.”

“He naturally refused.” Tomáš took a sip of absinthe and I waited for him to continue. “After your final performance at the PPI, I was surprised to hear that he was open to reconsider.” I nearly dropped my glass. “It was he that…broached the topic, as well. Something had changed for him. He has not reconsidered, mind you. He merely suggested that he would reconsider, however, on the condition that you do some…errands, some—” With his left hand, he paddled invisible waters. “— some…little things for him, first.”

At first, the idea seemed strange. Our reconciliation was conditional upon me running some chores for my brother. But as Tomáš told me about Worm’s first two requests—the third and final remaining unknown until the completion of its predecessors—it started to make sense to me. As calculated as my second baptism, submerged in the accumulation of tears on the altar of the PPI stage, Worm would continue to test my redemption. I gathered that if I could prove to him—off the stage, devoid of a director’s blocking, without his words to guide me—that I’d renounced the sins of my youth, become thoroughly repentant and shamelessly sought salvation, I was at least deserving of equal treatment by him. Without a modicum of consideration, I agreed.

“Very well,” he said, raising his glass. “To three simple requests for the reunion of the Brothers Wood.”

Download the PDF:

&I Cutting