When I look over the scope of a fairly intensive project, it’s pretty daunting. I see a colossal list of components for a design and try to comprehend how I’m going to manage it all. And with most design projects, each successive layer builds on the previous one.

For instance, you start with a thousand different thumbnails, each with varying potential for the basis of an identity. The client selects a handful of ideas and you create a thousand different sketches for variations on each concept. One (or few) directions resonate with the client, so you select the sketches that are the most promising and create iterations from that concept. The identity is selected so you develop and refine it further until it’s at the point where you and the client feel it’s perfectly polished. Then you version the identity, creating files in RGB, CMYK, Pantone, Greyscale and Black-and-white, bitmap and vector, EPS and TIF, tagline and no tagline, etc., etc. Now you’re ready to begin again, this time thumbnailing for the stationery system. And so on, and so on, until you have established the strongest campaign for branding, print, web, advertising and all other media.

Needless to say, it’s an addlepating process. And in the past, with each step, I felt an increasing agitation toward completion. You see, I’m a product of the instant gratification generation. In my youth, I saw the advent of on-demand television shows, instant downloads, beepers, 24-hour support lines, overnight coast-to-coast delivery, cell phones, texting, and other burgeoning technologies. They’ve stifled my need for patience and decimated the satisfaction that comes with time-sensitive cultivation. I had a rock tumbler as a child and never used it, because the dang thing needed to spin for two weeks before the jagged, lapidarian detritus of the world was metamorphosed into a wondrous semi-precious stone. I had no interest in buffering screens and download estimations. I wanted it now and I wanted it perfect.

The same issue flogged my work. With the arduous and time-taxing process I outlined before you, you can almost feel the anxiety in my tone. It’s long and stressful and uncertain. Who knows if on step 45, I’ll realize an irreparable flaw back in step 2? If I didn’t love it so much, I might as well throw up my hands and become a family portrait photographer, a short order cook, a cab driver, or some other profession that lends itself to snappy productivity. Needless to say, I’ve been dueling with this for considerable time, which has only served to compound the issue (as it’s, yet again, something I cannot resolve quickly).

Well, my neighbor and good friend recently threw away a canvas, which I rescued from the trash. And, upon questioning her about it, she told me: “I have no time to paint, anymore. You do something with it.” Naturally, I took this as a challenge. So I ransacked my house for paints only to discover that I had 12 tubes of aging, unused oil paint that I’d also rescued from the streets. If you’ve ever used oil paint before—which I hadn’t—you know that it’s a lengthy process requiring days of drying time between each application.

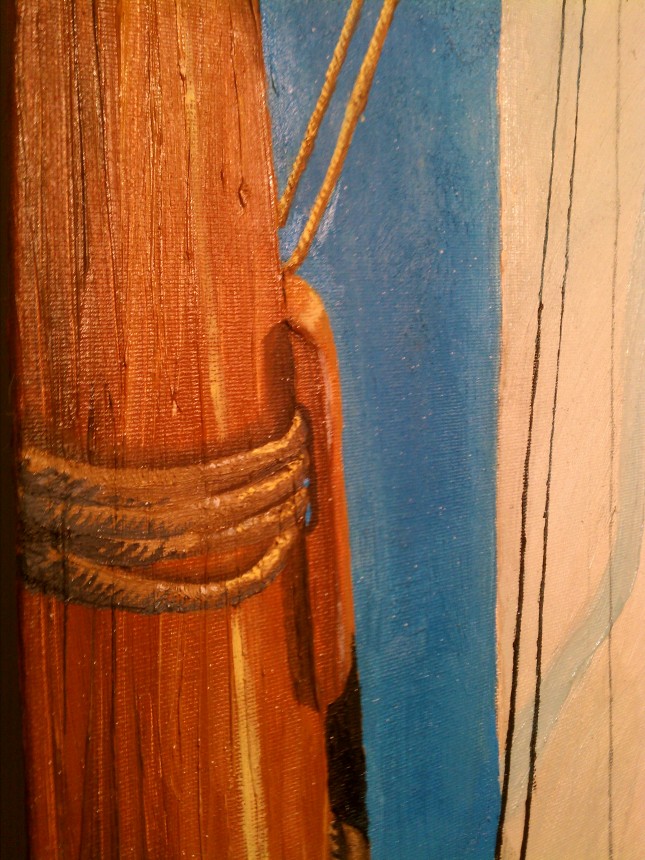

So I laid a drop cloth over my kitchen table and I began to paint a sailboat for my neighbor. The first night, I looked at the glistening canvas and said “this is going to take forever!” I cursed the name of every Italian renaissance master that I could remember. Then I invented some Italian-sounding names and proceeded to curse them too. Then I walked away from the canvas.

The following day, I studied my progress. I pored over the brush strokes and examined the subtle mixes of color in the morning sunlight. I made mental notes of the places that were in need of reparation, the places that had a solid foundation, and every possible issue I saw with the piece. And as I was beginning to feel the daunting, telltale signs of stress familiar to those with work and life, I felt a strange sense of accomplishment.

“I’m oil painting,” I said, aloud. I’d never done it before and was actually really excited about the small steps I was making toward the painting’s completion. In examining the daily progress, the evening before abandoning the painting and the morning after, I felt a gratification for the process and was no longer yearning for its completion. “This is going to take forever to finish,” I remember saying. But in that sentiment, I felt joy. I hadn’t wanted it to end.

After an embarrassingly undisclosed number of nights, I considered the painting done (or, as Paul Valery would say: abandoned). There was a little sadness when the project finished. It was surprising because I’d grown accustomed to the impatience I’ve felt in completing a design for work and the overdue gratification that occurred when it finally was done/abandoned. I sat down at my computer that morning and the list before me didn’t seem quite as daunting. And as I crossed each step off along the way, I began to feel the satisfaction for the process—much the same as I had with the painting—rather than the ache for closure.

Not to sound prophetic, but the experience reminded me how we should spend our lives: enjoying the days we’re alive and caring, but not necessarily focusing, on the end of the project, so to speak. An eschatological view of design is a fatalistic one.

With each new design that I’ve worked on, since completing “Adirondack” (detail above) I am reminded of the little pleasures of the process and how much I enjoy the journey so much more than the destination. I think of the scope of each new project as a path littered with countless, unseen treasures and no longer dread workdays devoid of completion. In fact, despite endeavoring to consistently meet deadlines, I now prefer the days that end without the project ending. Without sounding cliche, my neighbor’s trash has certainly become a lesson to treasure.